In 2018, Italian billionaire Leonardo Del Vecchio returned to the city of his birth and offered to invest €500m in the country’s main cancer hospital.

The refusal by Milan’s Istituto Europeo di Oncologia to accept the money set the stage for a battle that is now being played out at two of Italy’s most important financial institutions: Mediobanca, long a powerbroker in the country’s corporate sector; and Generali, Italy’s biggest insurer.

Del Vecchio, who is founder and chair of the world’s biggest eyewear business Luxottica, took the rejection as a personal slight and blamed the hospital’s biggest backer, investment bank Mediobanca. This has led to tensions between Del Vecchio and the bank’s chief executive, Alberto Nagel, according to several people with knowledge of the relationship.

“The animosity between Del Vecchio and Nagel goes back to the aborted investment. That is where all these tensions began,” said a prominent Italian businessman who knows both well.

Del Vecchio, a significant investor in both Generali and Mediobanca, has challenged Mediobanca’s reliance on its 13 per cent shareholding in Generali for profits. At the same time, he and other Generali shareholders are engaged in a tug of war with Mediobanca over the future of the group and its management under chief executive Philippe Donnet.

A key ally in Del Vecchio’s campaign against Generali’s management team is Francesco Gaetano Caltagirone, the 78-year-old construction tycoon who is deputy vice chair of Generali and is also an investor in Mediobanca.

In September, Caltagirone and Del Vecchio, the insurer’s second and third-largest shareholders behind Mediobanca, signed a formal pact with another smaller investor to consult on decisions ahead of Generali’s annual meeting next April. The group collectively owns 14 per cent of its shares.

Generali’s strategy day next month, when investors will hear its three-year plan, will be a “watershed moment” in the shareholder battle, said Andrew Ritchie, a senior analyst at research group Autonomous.

He expects “more of the same” from Generali, focusing on earnings growth and investor returns, adding: “That will require a response from the agitating shareholders to say what they could do better.”

This tussle for control involving two of Italy’s leading finance houses and a pair of ageing billionaires highlights the personal rivalries and entangled shareholdings that dominate the country’s financial sector. “This is not a battle for power, it’s a battle for efficiency,” said a spokesperson for Caltagirone, who has increased his stake in Generali from 1 to 8 per cent during the past 12 years.

Del Vecchio’s role as a power player in the industry came relatively late in his career. Soon after his donation to the Milan cancer hospital was turned down, he took the Italian financial world by surprise when he announced a 7 per cent stake in Mediobanca. He now owns just under 20 per cent, the maximum allowed under an agreement he reached with the European Central Bank.

He has used his position as Mediobanca’s largest investor to push for governance reforms and has also put pressure on Nagel to reduce the bank’s reliance on the dividends it receives from Generali, where it is the biggest shareholder, and from Compass Banca, a consumer credit company.

Up to a third of Mediobanca’s revenues come from its Generali holding.

“For the first time, Nagel has been put under pressure to really do something,” said a close ally of Del Vecchio. “People think this is the final showdown — there is an atmosphere in the air that something needs to change.”

Under the pact between Del Vecchio and Caltagirone, the pair have agreed to consult each other on how to achieve “more profitable and effective management” of the insurer.

The banking foundation Fondazione CRT has also signed the pact, and Del Vecchio and Caltagirone hope the powerful Benetton family, who own 4 per cent of Generali shares, will join.

The alliance has put Del Vecchio and Caltagirone on a collision course with Nagel and Mediobanca, who back Generali’s management. Mediobanca has responded by borrowing 4 per cent of Generali’s shares, increasing its stake to more than 17 per cent. Mediobanca’s voting rights on the borrowed shares will expire just after Generali’s AGM.

To complicate matters further, Italian MPs recently proposed a legal reform that would in effect put a six-year limit on the tenure of top company executives and board members. This would affect Donnet and Gabriele Galateri di Genola, Generali’s chair since 2011, and could matter for Nagel in future.

Generali’s approach to technology and its M&A strategy are two points of disagreement between the insurer’s management team and the alliance of aggrieved shareholders. A person close to Delfin, Del Vecchio’s holding company, called Generali a “fintech laggard” and said its recent dealmaking was a “mixed bag of small-scale flag-planting and doubling down in traditional Italy, where it already dominates”.

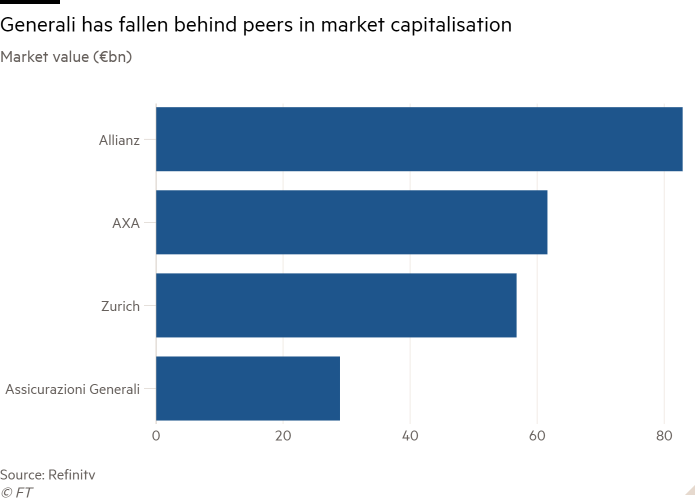

Critics view Generali’s recent acquisition of troubled local rival Cattolica as the kind of deal that is better for the Italian economy than for Generali’s shareholders. People close to Caltagirone said the Cattolica deal was “too little too late”. Generali has fallen behind peers in market capitalisation terms over the past two decades.

“Generali needs to find a way of growing organically or [through M&A] which keeps it on a par with the likes of Zurich, Axa and Allianz, who have all taken a lead over Generali if you look back at the early 2000s,” said one large shareholder.

But supporters point out that Generali’s shares have generally done better than rivals since Donnet’s last strategic plan was launched three years ago. Generali’s stock is up some 24 per cent since then, compared to 5 per cent at Allianz, 15 per cent at Axa and 25 per cent at Zurich.

Another criticism levelled at Generali is that Mediobanca, its largest shareholder, has outsized influence over the insurer. Generali’s long-time chair, Di Genola, had been Mediobanca’s chair until 2007.

Generali declined to comment for this article. But a person with knowledge of its view said the narrative of Mediobanca’s sway over Generali was “outdated”.

“If you look at the business decisions that have been made by Generali — M&A, strategic, you name it — it is impossible to see where something has been done to the benefit of one specific shareholder rather than all shareholders,” the person said.

Del Vecchio and Mediobanca also declined to comment.

The question is whether any new strategy can win over Generali’s rebellious shareholders — or at least stop institutional investors from rallying to their side.

Another person close to Generali’s management accused Del Vecchio of “strategic infantilism”, adding: “He wants Generali to become the largest insurance company in Europe, if not the world, but how to implement that is not clear.”

A former chief executive of an Italian finance group said he did not expect the two sides to reach a compromise before the AGM. “The billionaires will never give up,” he said.

“Too much money is at stake, but also as they reach the end of their lives, their reputation, legacy and pride are at stake. It is very difficult to find a compromise with them.”

Additional reporting by Stephen Morris in London